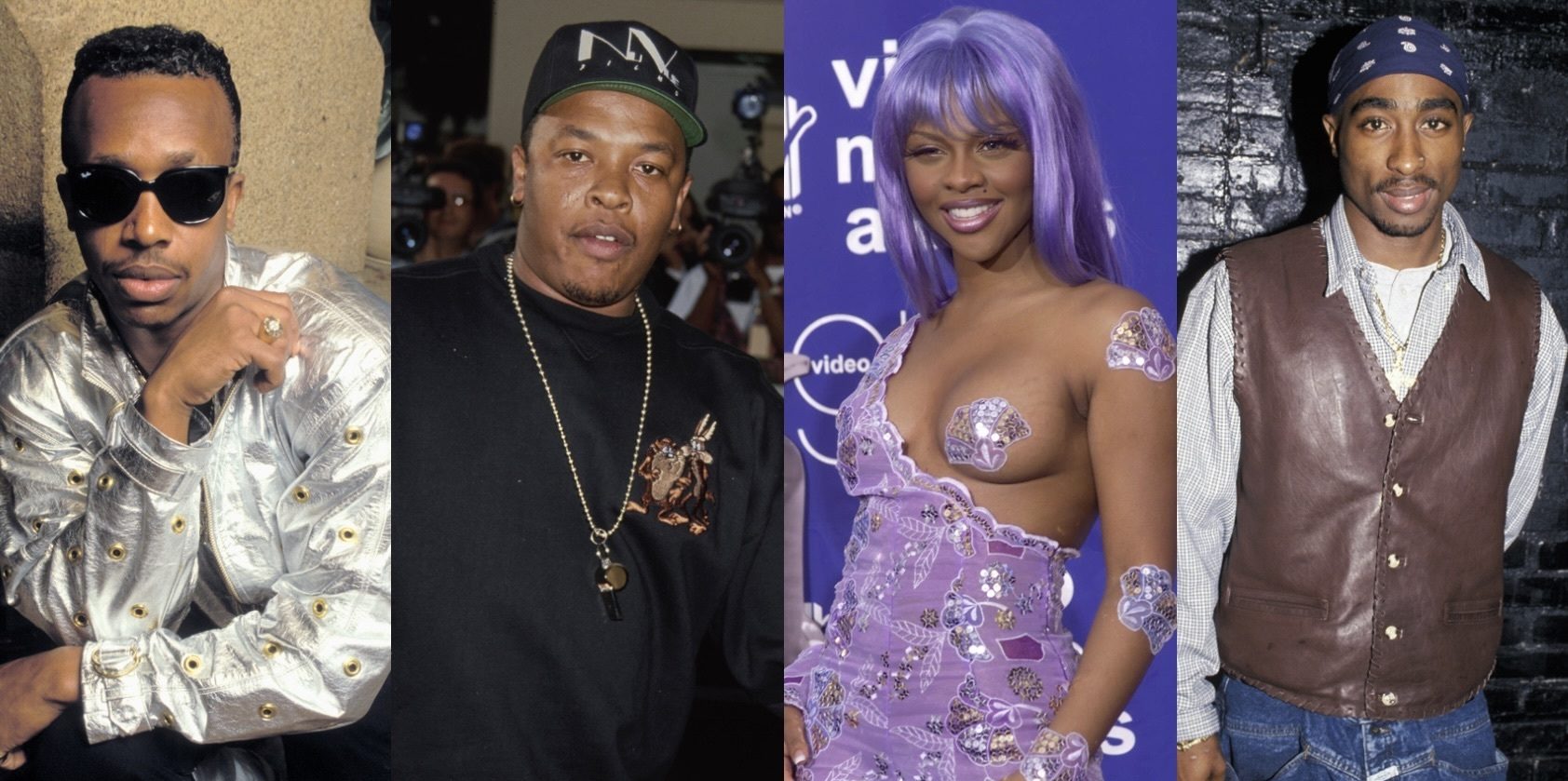

Photo: Frans Schellekens/Redferns, Vinnie Zuffante/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images, Scott Gries/Getty Images, and Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images

In honor of Hip Hop’s 50th Anniversary, The Shade Room would like to commemorate the moments, the pioneers, and the tools of the art form which have ultimately transcended the music genre, influencing every aspect of modern-day popular culture. Join us each week as we look back at five decades of hip hop.

Starting the list, we have MC Hammer knockin’ doors down by becoming the first rapper to have a diamond-certified album.

According to the National Museum of African American History & Culture, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) certified the project as diamond in April 1991. This notably went down merely one year after its release.

MC Hammer acknowledged the album during a 2020 sit-down with HipHop-N-More to mark the project’s 30th anniversary.

“You know, the title of my album was Please Hammer, Don’t Hurt ‘Em, I think a lot of them are still hurt. I think that for people who were competing against me at that time, like if you look at it from a sport standpoint, they were competing for record sales, right? They didn’t come close in that area. Then they were competing for cultural impact.”

This accomplishment opened the door for other artists and shut down critics of the genre. In later years, additional hip hop albums that went diamond include The Marshall Mathers LP by Eminem, Country Grammar by Nelly, Speakerboxxx/The Love Below by Outkast, and other hit albums by artists like Tupac Shakur, The Notorious B.I.G., and Lauryn Hill.

We should also add that, per Billboard, Please Hammer, Don’t Hurt ‘Em is the hip hop album that spent the longest continuous time at #1 on the Billboard 200 (18 weeks). As a result, it’s only fitting to give this game-changing project its flowers!

While speaking on hip hop in the 90s, we’d be remiss not to acknowledge how the rap remixes of the time truly served up something special for listeners.

Plenty of bops continue to get remixed, though this often involves the track being the same with a rap verse plopped in.

However, back then, listeners could rest assured that remixes would serve a completely different vibe. Some of the tracks that spawned noteworthy beat-switchin’ remixes include “Scenario” by A Tribe Called Quest (1991), “All I Need” by Method Man (1994), and “Street Dreams” by Nas (1996).

Another instance of a significant switch-up is Lil’ Kim’s spicy “Not Tonight” track (1996) turning into a fun-filled bop through its “Ladies Night” remix (1997) with Angie Martinez, Missy Elliott, Da Brat, and Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes.

Even some of the R&B superstars got in on the vibe. Brandy featured MC Lyte, Queen Latifah, and Yo-Yo on the hip hop remix to “I Wanna Be Down” (1995), which Norwood said “meant the world” to her, per Vibe.

“They embraced me as a little sister. I was one of the first R&B artists to welcome hip hop onto an R&B beat. It had never been done before quite like that.”

The “Remix Queen,” Mariah Carey, also came thru with hip hop remixes featuring artists and groups like Ol’ Dirty B*stard (ODB), Da Brat, Missy Elliott, Mase, and The Lox — showing the R&B diva effortlessly getting into her rap bag and sampling artists like Snoop Dogg!

Of course, we also have to give a special shoutout to the female rappers who began to hit the scene around this time, as they truly laid a foundation and played the game while bringing their unique vibes.

From Da Brat’s Funkdafied (1994) to Lil’ Kim’s Hard Core (1996) and Foxy Brown’s Ill Na Na (1996), the gworlz came thru and let male rappers know that they were here to change things up!

We also had Lady of Rage laying down bars on Snoop Dogg’s Doggystyle project (1993) and Ms. Roq having a MOMENT on Dr. Dre’s 2001 album (1999). Trina also hit the scene in the late 90s by hopping on “Nann” (1999) with Trick Daddy.

Around the same time, works like Joan Morgan’s When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost (1999) highlighted hip hop’s male-centric core, and more women began unapologetically hitting the rap scene and turning the genre on its head with their savage flows.

Lauryn Hill was another artist who hit the scene during the 90s with the Fugees. Her solo debut with The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (1998) earned her the title of being the first woman to earn ten Grammy nominations (and five wins) in a single night. She also claims the title of being the first hip hop artist to win Album of the Year.

While earlier women in the game helped shake things up, female rappers began to really carve out a lane for themselves as a force to be reckoned with during the 90s.

It wouldn’t be 90s hip hop if we didn’t touch on the East Coast–West Coast rivalry centered around figures like Tupac Shakur, Suge Knight, The Notorious B.I.G., and Diddy (then still known as “Puffy”).

While there were some jabs here and there between artists reppin’ New York City and Los Angeles, the situation escalated after gunmen shot Tupac while entering Quad Recording Studios in Manhattan on Nov 30, 1994.

It was on then, and various disses at the 1995 Source Awards and a notorious NYT article ensued. Tupac also made his stance clear across multiple diss tracks and infamously went in with “Hit’ Em Up” (1996).

Eventually, the coastal rivalry and deep-seated beef culminated in the deaths of Tupac and Biggie in Sept. 1996 and Mar. 1997, respectively.

Both killings remain unsolved. However, as The Shade Room previously reported, there’s recently been some renewed interest in the Tupac case.

Finally, we must acknowledge how the genre made leaps and bounds in the business realm during this decade. Ultimately, this helped turn hip hop into a billion-dollar industry.

Regarding how business and marketing play into hip hop, C. Keith Harrison, a business professor at the University of Central Florida, notes that — at its core — the genre “has always been about the audience.” Over time, we’ve seen it move from “being marginalized” to “becoming hyper-commercialized.”

“It goes back to ‘Throw your hands in the air, and wave ’em like you just don’t care.’ It’s gone from being underground to being marginalized to crossing over to the mainstream to becoming hypercommercialized.”

Master P built on this by launching No Limit Records in 1991. One of the label’s best-known releases is Snoop Dogg’s Da Game Is to Be Sold, Not to Be Told (1998).

Dan Runcie — founder of Trapital, a “research group focused on music, media, and entertainment” — spoke on the business side of hip hop during a recent sit-down on The Hustle Daily Show.

At one point, he acknowledged how there was a significant shift in the business of hip hop during the 90s. He honed in on Dr. Dre and Death Row Records, founded in 1991.

“Dr. Dre stands out to me from what they had done with Death Row. In the 90s, we started to see more evolution with the economics of the music industry itself and how artists — especially hip hop artists — started to approach things differently. … In hip hop, we saw a few artists start to push for more ownership of the masters and actual assets they had. We saw it first with Death Row Records. Suge Knight and Dr. Dre do a deal with Interscope where they’re able to maintain ownership of what they have. This was the early 90s — they sat on Dr. Dre’s debut album, The Chronic, for nearly a year because they wanted to find the right distributor.”

Fast-forwarding to 1998, Runie discussed Cash Money Records signing a $30M distribution deal with Universal, calling it “probably the most successful ownership-related deal we’ve seen in hip hop.”

He also acknowledged, “That deal set the footprint for arguably one of the most successful record labels we’ve seen.”

Of course, we can’t forget to mention Jay-Z and Damon Dash’s Roc-A-Fella Records. This label came about in 1994 “because Jay-Z could not find a suitable record deal,” according to Icons of Hip Hop: An Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, and Culture.

Aside from hard-hitting record labels, the 90s also saw the emergence of Black-owned fashion brands that were inextricably tied to hip hop — such as Daymond John’s FUBU in 1992, Russell Simmons’ Phat Farm in 1992, Diddy’s Sean John in 1998, and Jay-Z’s Rocawear in 1999.

Regarding FUBU, Daymond appeared on The Ellen Degeneres Show to discuss rappers helping him grow by rockin’ his brand.

“I would go to every video set I could over the course of 10 years with the same 10 T-shirts. And I’d put a T-shirt on a rapper, and then I’d take them back. And then I’d keep going back to the sets … people started seeing them in the videos.”